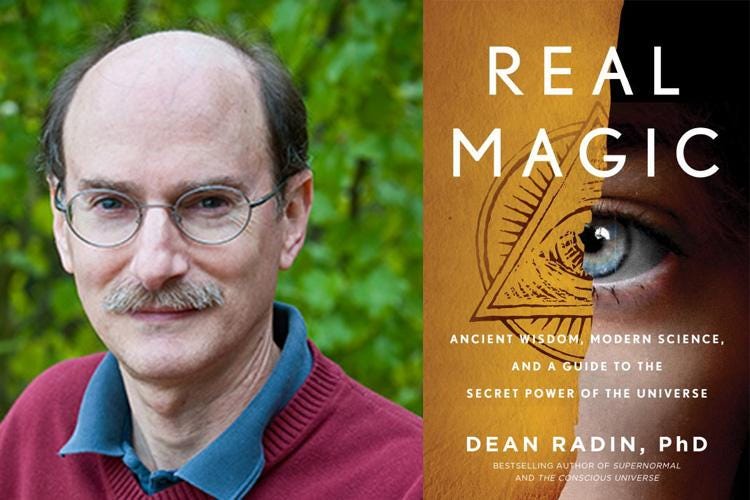

Scientist and author Dean Radin, who has published many books on psi-related topics, discusses his new book Real Magic: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Science, and a Guide to the Secret Power of the Universe. First question: How can we “trust the science” when it simultaneously tells us that “magic works” (i.e. psi is real) and denigrates its own findings? Below is a rough transcript of the interview.

Kevin Barrett: Hi, I'm Kevin Barrett of Truth Jihad Radio saying that you don't need to be a psychic to know that the commercial messages being beamed into your brain by advertising are extremely annoying. That's why the advertising model for internet radio sucks. There's got to be a better way. Well, there is. It's called the subscription model. Please go to TruthJihad.com and subscribe by way of the "Subscribe at Substack" button.

Welcome to Truth Jihad Radio, the radio show that has no respect for the taboos that prevent us from trying to figure out the truth about all sorts of very important issues that aren't being properly covered in the mainstream. I'm Kevin Barrett. We talk about politics a fair bit on this show, social issues a little bit, and occasionally even science. And we are now in a strange phase of cultural development in which we are being browbeaten to "trust the science." Well, I trust the scientific process to a certain extent. It's a good method for trying to figure out certain kinds of empirical things. But there are a lot of problems in the scientific community, and one of them is the reluctance to acknowledge the results of a very rich history of psi experimentation. I discovered this in high school by reading the Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on ESP. I did some research and I was shocked that so many people know that things like telepathy and precognition exist, and yet the larger scientific community tends to deny it to a certain extent—even though science itself has proven it seven ways from Sunday.

And one of the world's leading experts on all of this is Dean Radin. He's the author of a long list of great books, including Super Nature and The Conscious Universe, which is a really good primer on these topics. He has a new book out called Real Magic, which I haven't read yet, but I'm intending to. He's been doing entangled photon experiments, among other things, and offering great commentary on his Twitter feed and website. So, hey, welcome Dean Radin. It's great to have you back.

Dean Radin: Glad to be here, Kevin and my last name is pronounced "Raiden."

Kevin Barrett: I'm sorry. I'm thinking of Paul Radin, the French anthropologist, and I guess I got the pronunciations confused. Are you of French ancestry?

Dean Radin: No, we're probably a different family tree. I think my last name used to be Radinsky when my grandparents or one set of grandparents emigrated from Russia way back when.

Kevin Barrett: Oh, very interesting. Ok, well, I'll try to keep that pronunciation straight. So Dean Radin...Here we are in a very strange cultural moment with a pandemic raging around us or maybe raging a little less than some pandemics in history have. The cultural issues around it are certainly raging. And the leitmotif "trust the science" is everywhere. Well, Dean, you do science, you're a scientist. And yet you've noticed that the scientific community, when it gets into sort of a groupthink bubble, is often wrong. So we could start by hearing your thoughts about that.

Dean Radin: Well, science has an aspiration for the same as we see in the academic world for academic freedom. That means that you can apply the the tools and methods of science and scholarship to study anything that you want. But as we all know, the aspirations sometimes are not actually realized. And it's just as true in science as it is in any other enterprise that involves more than two people, which is basically everything. So science has its own sets of taboos about what you're allowed to talk about. It is definitely influenced by politics, and strongly influenced as well by business interests. And so I think one of the reasons why a lot of people today, in considering the pandemic, they're suspicious about science because there's also an assumption that not only are there external influences which determine what the mainstream believes—and by the way, there is no one mainstream, there are dozens of them—but also there's an assumption that when the scientists, especially within medical science, make a pronouncement, then that's the way it is. But that's never the way it is. Experimental science is always provisional and theories are always provisional. The reason why I think it's useful to pay attention to what science actually says is because it means, that phrase means: "Is there evidence to support the conclusion?" Well, evidence, too is uncertain. It's only at the stage when something turns into technology that we have extremely high confidence that our theories are correct. But all of the really interesting questions out there are still very much in the theoretical phase, or there's experimental data which is not yet clear. So I understand why people who are not scientists are reluctant to pay attention to it, because after a while, they don't know who to pay attention to any more. So I have great sympathy for that.

Kevin Barrett: Yes, I do, too, and I share some of the confusion. I've been a humanities scholar; I taught humanities for a while at a community college in the Bay Area and had to deal with conflicts between science and the human centered disciplines. And there's no really clear, simple way of interpreting and mediating all these disputes. But you mentioned that when science turns into technology, that's when we get a high confidence in that particular area. And why hasn't psi turned into technology?

One paranoid conspiracy theory, which, like many others might be true, is we could imagine that if a particular group ever managed to turn psi into a reliable technology, they would want to monopolize it. And part of their strategy for monopolizing it might include pooh poohing it and making sure that the serious people in the culture didn't believe in it, so nobody would ever replicate their technology. That's one possibility, of course. And there are others as well. So why has psi, which is so well proven scientifically, not yet turned into technology that we've heard about?

Dean Radin: Well, it's as you say, that there are a number of answers to that, and they all conspire in such a way to put us in the middle of a paradox. The paradox is that when you do surveys of people in terms of their experiences— we did a survey where we had 25 different kinds of experiences that people report, but we didn't use any of thoe psychic terms. We didn't use terms like telepathy or precognition. We simply described the way that the experience could happen to somebody. And then we asked the general population and a subset of scientists and engineers how many of these 25 different kinds of experiences have you personally had? And so among the general population, ninety four percent of people said they had at least one of the 25 and an average of about seven of the 25 different experiences that they personally had. And this is why when you ask people about their beliefs and telepathy or precognition, the majority of the population believes because they've had that experience themself or they know somebody that they trust who reports such experiences. So our surprise was when asking the same question to scientists and engineers, again, 93 percent and on average, actually more than the general population—on average eight of the 25 experiences, scientists and engineers have had personally. So this is supported by what we see in the laboratory, because oftentimes when we do an experiment on one or another kind of psychic phenomenon, sometimes we select people based on maybe they're a meditator or maybe they report these experiences, but oftentimes they're unselected. They're basically the person off the street who we recruit to do an experiment. And they can show results, too, usually not as good as somebody who's selected, but nevertheless, it seems like this is a natural ability that most people have, whether they realize it or not.

So the paradox, then, is the very commonly reported and scientifically confirmed experiences that are not part of the academic dialogue. And so then the question is, well, why not? It is certainly part of our entertainment business. It saturates our books, it saturates television and movies. It's as though we're in the emperor's new clothes, that everybody can see what's happening, but people aren't willing to talk about it. So why is it not in the academic world? Well, the academic world today is the result of the Enlightenment, and part of the Enlightenment was development of the philosophy of materialism as a way to understand the nature of reality. And from a materialistic perspective, it's very, very difficult to understand how something like telepathy could exist or how something like precognition could exist. And as a result, you do find leading spokespeople today within the scientific world who echo this idea that as far as they can tell, by their understanding of the physical world—(this is) even said by physicists who should know better—they say that the world, as we understand it, does not allow for these phenomena. Therefore, anyone who reports it is either lying about it or they're mistaking coincidence or they don't understand probabilities or one of another dozen kinds of explanations. And then you have to put in religious pressure against looking at these kinds of phenomena, and you put in governmental pressure, because they don't want secrets to be spilled. Lots and lots of reasons conspire to maintain the taboo in the academic world.

Kevin Barrett: Do you think philosophy has a role to play in changing this situation? I recently read Bernardo Kastrup's book Materialism is Baloney, and it's a very good, concise refutation of materialism and basically follows the same lines of thought that I've been following for decades. But he says it far better than I ever have. So do you think that a serious consideration of the philosophical issues could change this kind of strange form of dogmatic, materialistic scientism that we're experiencing today?

Dean Radin: Absolutely, it could. And the thing is that when you ask people who are trained as engineers and scientists, how many courses on the philosophy of science or the sociology of science have they had? And the answer typically is done. And some scientists even go beyond that and say, we don't need philosophy. Philosophy has been doing this for 3000 years and hasn't gotten anywhere. So who needs philosophy? Well, that's a problem, because as all fledgling scientists know, when they go through their academic career, they're never told that what they're studying is resting upon large sets of assumptions. And assumptions are just that. They're ideas that we accept because they seem to be useful at the time. So as a student, you don't know you're being trained in materialism. And even worse is that even our concepts of what we mean by material have radically changed over the past century. So if you don't have at least within your own discipline, a really solid background in the history of the change of assumptions in your own discipline over time, then you won't understand why there would be so much resistance to changing the idea. After all, materialism is extremely successful. We're not going to drop it no matter what. What we probably will do, I think, is recognize, as we have done in every other discipline in the academic world, that our set of assumptions today is probably a special case. Just like classical physics is a special case of a more comprehensive way of thinking about reality. Well, the same is true about materialism. In general, it works really well, but only in certain circumstances. And as we begin to expand our concept of what we're going to study, including things like consciousness and subjectivity, we need to expand our assumptions about how reality works. And you can actually see that today, even in physics, where there's a growing number of physicists working at the edge who are trying to define what do we actually mean by reality? And so the old idea that maybe our mind or consciousness is wound into physical reality in some inexorable way is now no longer a taboo topic to talk about. So that's that is showing actually there is a slow change in terms of redefining what we will accept in terms of our assumptions.

Kevin Barrett: It does seem that a lot of relatively mainstream people admit that the hard problem of consciousness is real and that any solution to it may require a bit of a paradigm shift. So maybe that's a sign that we're getting closer.

Your new book, Real Magic, sounds like it does touch on the topic of people who have sort of instrumentalized these psychic phenomena in a way that would be sort of like what would happen if we technologized it and made it therefore scientifically real. It occurs to me that maybe such developments would have a downside as well. Part of the reason that so many people are resistant to this is: who wants to think you're living in a world where people can read your mind, especially really gifted people, and you're not one of those really gifted people? So there's somebody out there who can read your mind and you can't read his mind. That's bad news. And push it one step further and we're in Philip K. Dick's World, where— I don't know if you've read Philip K. Dick's science fiction novels, but in quite a few of them, we have essentially corporate capitalism has gotten even worse in the future, exploiting other planets, in some cases in hideous, nightmarish ways, very similar to the way our current culture is exploiting so many things.

And in these novels, there are precog bureaus where wealthy people can hire a precog to tell them which way the future is going to go. And they're using this for the same reasons that corporate executives today might, say, hire a mafia hit man or something, you know, it's purely self-interested, purely in search of money and power. And so allowing these abilities into the culture and getting them instrumentalized and turned into technology or real magic, as your book title suggests, might have that kind of downside. And one wonders whether there could even be benevolent entities or, you know, a law—even in my Muslim paradigm—that would be dictating that progress towards this is somewhat slow—that people's egos have to be set aside. The Sufis say you need the annihilation of the ego to get into the state where you're seeing these other levels of reality. And so maybe there's a built-in limit to it. What have you speculated on the various ways that this development towards technologizing psychic powers might not be such a good thing, and on the possibility that even relatively benevolent forces as well as malevolent ones could be suppressing them?

Dean Radin: Well, it's already being used. Estimates of how much money the quote psychic industry makes—it's in the billions of dollars a year now. Most of those are psychic readers who may or may not have any talent. Some of them do. But within the corporate world and in government, there are plenty of consultants who do work for people who are wealthy. And in governments that's already happening. It's just it's flying below the radar.

Kevin Barrett: So the Genie's out of the bottle and the cat's out of the bag. Deal with it.

Dean Radin: It's quite clear there are some people who are very talented in these kinds of things, and so they're being used. They probably always have been. So what you're talking about are other pressures, like why, well, why isn't this common knowledge? Well, it kind of is common knowledge. I mean, it doesn't take much Googling to find out that this is true. The question is, why don't we have departments in universities that are talking about these things? So some of it you already touched upon where our government and business industries and law would not work if there were no secrets. And so if this became widely known, and the methods for enhancing telepathy, for example, became common through technology or psychedelics or something, that would be a very serious problem, because you can't sustain government or modern civilization in any form if everybody knows what's actually going on. So you have the status quo saying, "Oh no you don't, we don't talk about these things, it's too dangerous." And a lot of pressure can be brought to bear...Anybody who is in a position of authority to talk about what's real is either declared to be demonic, you're not allowed to touch it, or the academic equivalent of demonic, which is a taboo which says this doesn't exist.

So lots of pressure from many different angles would make it very difficult to allow this kind of effect to go mainstream, at least in terms of the general population believing that it's being used in some way, even though privately they are using it; more evidence of this strange paradox that we find ourselves in, where basically everybody has had these experiences, most people believe in it, it's being used to the tune of a billion dollars a year. And yet officially—and by officially, of course, what we're talking about are major scientific journals, science, popular science journals, large newspapers and so on—there's a very common spin that is provided in all of those sources, including Wikipedia. So the average person wants to know: I had a weird experience last night. What does that mean? Well, they search all the usual places. They're going to come back with saying it's just an illusion, it wasn't a real thing, after all. But that's simply wrong. So, yeah, the status quo doesn't like these kinds of ideas and it pushes back hard.

A case can be made by the way, that during the Cold War, when the U.S. government had Stargate, which was psychic espionage, and other programs going on, it was working really well. And it continued to work really well for two reasons. One, it was top secret, so very few people knew of its existence. But at the same time, if you have a secret weapon, so-called, it is to everyone's benefit for everyone else to either not know that you have a secret weapon, or they are told that the secret weapon actually doesn't work at all. So it's difficult to prove that there was pressure or influence from the government to support skeptical societies that made it their business to constantly say that none of this stuff is real. But I would not be surprised if historically we find out at some point that there were links from our own government to create a public narrative, just as it did with UFOs, that there's nothing to look at here. Just keep going about your business. None of this is real. Because on the inside, they knew that it is real and actually quite important. So it's like a classic deflection maneuver.

Kevin Barrett: And a book that could be seen as a deflection maneuver or as this kind of limited hangout, or even in some ways, a revelation, is Jon Ronson's book The Men Who Stare at Goats. And that, of course, does raise the same kinds of questions as I did when I brought up Philip K. Dick, about pretty malevolent power seeking psychopathic people at high levels of our power pyramid trying to get their hands on this sort of technology. And of course, Jon Ronson uses this as fodder for humor. It's kind of amusing that a bunch of special forces killers would all line up and stare at a goat and try to kill the goat with their brainwaves or their psychic ability. So he milks that for humor. You finish that book, though, and one impression you could get would be he's dismissed the whole topic because we're all laughing at it. It's so ridiculous. But (considering) the actual material in the book, especially the stuff at the end about some of the CIA's horrific experiments that have been proven to have actually happened, we realize that he's exploring an area that actually could be quite important. So I think humor is one element that's been used to sort of defang the topic. And that could be both positive and negative, I suppose. Did you see Ronson's book and the movie they made out of it?

Dean Radin: I did, yes. And in both cases, the book and the movie present a humorous side to all of this because it is kind of silly. On the other hand, both the book and the movie are revolving around issues that actually did happen. And both of them leave the reader or the viewer with the sense that, oh, this isn't just a hallucination, it's not just an illusion. There actually was real stuff happening. So it's interesting. Then, from a point of view of a writer, how do you tell a narrative that will capture the audience and maintain their interest? Well, he did a pretty good job in that way, right? I mean, how many novels, whether they're based on fact or fiction, get turned into movies? Not too many. This one had elements in it where you can almost see that he was writing a movie script. And that's indeed what it turned into. So, yeah, it's one way to to spin a tale.

Kevin Barrett: Yeah. And I like Ronson's work. I know some folks in the alternative knowledge community find him to be with the nefarious forces of coverup. But I think if you read him carefully, it's not quite that simple. Most of the time, there are some exceptions where he's been unfair to various people. But yeah, The Men Who Stare at Goats was a powerful book. And I think it is designed so that an average educated reader might not take the subject quite as seriously as they should when they're done, especially if they're a careless reader.

Well, let's get to this new book you have out: Real Magic: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Science and a Guide to the Secret Power of the Universe. I'm interested in that connection between ancient wisdom and modern science...cultures have often managed to create means of preserving social stability in a world where these psychic powers not only exist, but everybody knows they exist. I did my PhD research in Morocco on Sufi miracle stories, and I did collect stories of people who had had extraordinary psychic experiences in recent times. And I think that in general, essentially everybody in Morocco—well, there might be one or two brainwashed university professors somewhere who haven't figured it out yet or who have been reprogrammed—but virtually the entire culture accepts that these abilities are quite real and going on around us all the time. And that culture has built in some safety mechanisms. People who use psychic abilities for selfish ends of any kind are looked down on a little bit. If you have to go to the market to buy some special herbs and some weasel brain—it's actually hyena brain, but my Moroccan wife mistranslated it as weasel brain, which is used by abused wives to totally control their husbands, to essentially turn the husband's brain to mush and take him over as if he were a zombie—you know, people doing that sort of thing are looked down on and considered sort of socially marginalized and so on. And of course there are people doing really nefarious stuff as well, and they're even more marginalized and looked down upon. Whereas the shaykh, that is, the religious scholar, who has this ability of clairvoyance and the television station reports on this and follows him around asking him questions about what's going on in this place, in that place where they have cameras and he's telling them exactly what's going on there because he can see it through clairvoyance—that this sort of thing is OK. If the religious ideals and the religious discourse approve of it and it's not selfish at all, it's all fi sabil illah, for the sake of God, then it's basically fine, it's good, it's benevolent. And the Sufi saints, who are often religious scholars, are honored for this. But the people who instrumentalize it in a selfish way, especially in a very selfish way, are marginalized and looked down upon. And I'm wondering if you think Western and modern culture has any possibilities of developing some sort of safeguard system in the event that this stuff breaks out more than it has?

Dean Radin: It's a very good question. The same social acceptance you find in South American countries, and India, basically all throughout Asia as well. And I've talked to scientists and scholars in those countries about these things. And what's interesting is that if there's large social acceptance, then there doesn't seem to be as much need or interest in having scientific verification and understanding. I found this most dramatically in India. I'm not entirely sure why that's the case. But in the Western world, the U.S. and U.K., Australia and so on, there, the need for scientific verification of something that seems spooky seems to be much higher, even though there's so much higher skepticism as well—although even the skepticism is only in a small minority of people. As I said, over 90 percent, basically everyone, including scientists and engineers, have had these experiences. So there's some natural skepticism. I guess it's built in to our Western worldview, and that's why we turn to science and say, is any is this real, what happened in this case? But now I've diverged from your question. So if you remind me what the question was—

Kevin Barrett: I was asking about possible safeguards, because we don't really have a religious discourse that's survived in this culture. Our religion, secular, progressive materialism, basically (holds that) an individual should grab as much power and pleasure as possible in their own way. And as long as they're quote unquote, not hurting anybody, they should do any darn thing they want. And so that philosophy may work OK at a certain level. But if, like in Morocco, everybody knew that these psi techniques are available and are extremely powerful, that there are specialists who are really good at them, (so) if you want to get something done, go to the specialist. Well, today, if the powerful people want to get something done, they go to specialists and they do very nefarious, selfish things regularly. And rather than being relegated to the social margins and considered taboo and like bad people that nobody would want to deal with, these people rule the culture. So how do we get some safeguards so that we don't end up with all the rich psychopaths using this stuff and making the world worse?

Dean Radin: Well, they probably already are. That's one of the sad things about all this in the classified environment. They asked once if we were very successful and we created some amazing new technology or something, what would happen to it? And the answer immediately was it would disappear down a black hole and you'd never be able to talk about it again or even work on it. And you could never even admit that it existed. So I thought, Well, that's not good. If you look at the many grimoires that you can buy out there, books of spells, that's all about gratifying the ego. Half of the spells are love spells and the other half are money spells and power spells. All of that is about manipulating the world around you. And what is not typically said in the grimoires is that probably 90 percent of the spells would be considered black magic. Because if black magic is defined as overcoming the free will of another person, that would be black magic. And do you think then about how most people would want to use these capabilities? It does fall into the category of black magic. You're trying to influence others' behaviors, others' beliefs, others' perceptions, all of that to your benefit, to your sole benefit. Well, fortunately, it's not the only way you can use these things.

There are also a lot of spells for healing. And presumably healing is good, except that healing can be reversed as well. And of course, one of the fears is that maybe you could harm somebody at a distance. That's probably true. So how do we protect ourselves? Well, you can already go to a religious artifacts stores and buy all kinds of little statues of saints. A lot of people do that. You can buy amulets, you can buy all kinds of things. Maybe it'll increase the stock in tinfoil so you can line all of your clothes and hats with tinfoil. (laughter) The problem is that as far as the scientific research goes, we don't know of any way to definitively block any of these capabilities, whether they're perceptual capabilities or psychokinetic. Nothing seems to block it or to stop it. If you read books on psychic self-defense, mostly it's about how you psychically protect yourself: You surround yourself with white light or with a mirrored shield or things of that sort. Well, some people can do that, and other people are not very good at doing those kinds of things, in which case, unfortunately for many people, they actually will not be able to protect themselves.

Kevin Barrett: Muslims believe, and that would include me actually in my own way, that the final two short suras of the Quran, the Mu'awwidhatayn, provide powerful protection against this sort of thing. And along these lines, there is a very interesting case of a professor named (Ioan) Couliano, who I think he was Romanian, who wrote a book called Eros and Magic in the Renaissance, which looks into the simultaneous birth of science and a certain kind of magic in Western culture. And both the science and the magic may have been tending towards black magic and mass psychic manipulation and so on, which eventually created the world that we're in today. Anyway, he was mysteriously murdered in a University of Chicago restroom a couple of decades ago, I think. And they never solved it. Do you have any comments on that book or case or have you heard of it?

Dean Radin: I'm not familiar with that case, no. Maybe it's due to suppression in my own case, because you don't need to be accosted by too many paranoid schizophrenic who think that you're controlling their mind to want to stay out of the public restrooms. (laughter)

Kevin Barrett: Yeah, yeah. Well, Couliano was involved in some sort of political stuff as well. It's still a huge mystery what happened to him. But he was one of the leading scholars in humanities who was essentially taking for granted that these kinds of psychic abilities exist, though he wasn't putting it in the same sort of scientific language that you do. But he did take it for granted and was exploring a certain school of of practice of these things that emerged in the Renaissance. And then he had that strange death. And so a lot of folks were wondering what in the world happened to him and whether that's a bad sign for people in the academy who who study this sort of thing.

Dean Radin: So, yeah, as we've already discussed, it certainly raises concerns in a lot of people's minds about these things. They will begin to identify an individual who simply has an interest in the topic as suddenly being a dark magician or something like that. And if you look at the number of people who are mentally ill, who in one way or another think that they're also psychic, it's a pretty large percentage of schizophrenics, for example, who think that they're enormously psychic. And if they have a paranoid streak, they will flip out and they'll attack anybody who they think is involved in what they perceive as being psychic attacks on them. I mean, it's reasonable from inside their head, it's reasonable to try to get somebody to stop. And it certainly is not helped by the way that these kinds of phenomena are portrayed in entertainment. If you took any random sampling of 100 movies, for example, or television shows, that have a psychic component, almost all of them will devolve into horror films, and then that becomes part of the public way of thinking about these things. (The public) will think it in dark terms. And that's unfortunate, that those kinds of stories attract attention. I'm writing a TV series with a writing partner which has a very different spin on these kinds of effects, a much more positive way of thinking about these as simply natural human capacities, and most of the time, we just suppress them or we're frightened of them. And there's no reason to be frightened of them.

Kevin Barrett: Mm-hmm. Yeah, that's a good point. It seems that the same cultural forces that in the past marginalized these things through a religious discourse that claimed that this was all from the realm of the demonic, today are doing the same thing, just sort of disguising it a little bit. But the Hollywood narrative isn't that different from of some of the church narratives from the old days. I can certainly imagine a lot of ways of flipping that narrative, based on my own experience, for example, when I actually had the most intense set of these kinds of experiences that I've ever had. I've had occasional precognitive dreams and telepathic experiences like anybody else, you know, the phone rings and you know who calls, that happens every now and then. But I had a real, intense, maybe six months of that when I was in high school after I had visited Stephen Gaskin's Farm spin off in La Crosse, Wisconsin. Stephen Gaskin was a hippie spiritual teacher from San Francisco who led a couple hundred followers across the country in old school buses and settled on a farm in Tennessee. And then they had a spin off in Wisconsin. So when I was 16, I hitchhiked up there and spent a few days with those people. I think they'd been using psychedelics as well as mystical techniques. And they'd been systematically trying to create a community in which people sort of blow off their egos and experience loving telepathy and loving psychic experiences as just a normal part of life. And that group mind was so powerful that it kind of worked on me. So then when I went back home, I could still access that to a certain extent, and it was good. You know, the part of your ego that you're setting aside when you do these things is really kind of a prison. And it's a bunch of sort of mechanisms that force you to behave selfishly. And of course, maybe our ancestors needed mechanisms to force them to behave selfishly to survive. And that's why it's there. But freeing yourself to some extent from those mechanisms, stepping out into a space where you feel love and compassion for everything and resonate telepathically with other people, resonate with various kinds of of perceptions beyond the normal sensory perceptions, is actually a very positive thing. It feels good, and it feels like the sort of things that I've studied when I've studied the saints, the Sufi saints and other saints. So there seems to be a very powerful, positive side to all of this that really gets lost in the popular culture. How are you planning to to bring it back?

Dean Radin: Well, as I said through narrative, you can create different kinds of narratives to show that this actually is interesting from a scientific perspective and probably important if for no other reason than helping to augment the methods that we use in medicine, for example. We've done studies on energy medicine, which is by no means mainstream, except that slowly insurance companies are beginning to say, well, OK, it looks like therapeutic touch or Reiki actually does have some evidence for it. In which case if you get a Reiki treatment, maybe your insurance will cover that. So that's a major step in the direction of what amounts to a new and at the same time very old method of healing. We still don't really understand what energy medicine is, but it does seem to work and it's not placebo because you can do controlled studies too. So at some point, when we learn much more about what's going on in those kinds of methods of healing—some of which are psychic because it also works at a distance—well, that has the capacity for great good. And in many ways, everything psychic is just another kind of knowledge. Power could be used for good or bad. That depends more on how we want to use it rather than the power itself.

The same could be said for nuclear power or any other kind of power. It can be used for good or bad. It's up to us to decide. My long term view is that if if our species lasts long enough, we'll figure out ways of actually using these kinds of things in the same way we figured out nuclear energy and electrical power and so on. The downside might be that this is a kind of power that may not be suitable for an adolescent species like us; we're adolescent in the sense that we haven't been around that long, we still clearly have all kinds of things to work out before we can live peacefully together. And in that kind of culture, it's like giving bombs to babies. Well, they'll play with it, and they'll probably end up blowing themselves up at some point because they don't understand the power. And so that's kind of how I think where we are. The reason why I use the tools of science to try to understand it better is simply that the more we know about what we're dealing with, the better we will be able to handle this particular bomb and hopefully not blow ourselves up.

Kevin Barrett: Well, you mentioned healing being one of the obvious positive uses for this sort of thing. And today we're at a very strange moment where a certain scientific discourse is insisting that we solve the Covid-19 problem through one means primarily, and that is, everybody gets vaccinated. Of course, there are other scientists who question whether this is a sound strategy. And frankly, based on what I've seen so far, I would tend to side with those dissidents. But in any case, it looks like there's now a war on these pluralistic conceptions of healing. You can't put up a YouTube that discusses COVID or various other issues in a way that's perhaps not precisely in line with the W.H.O. or CDC without risking having your YouTube channel taken down for so-called medical misinformation. And even social media is now relentlessly patrolled for so-called medical misinformation. I can imagine that anybody promoting any kind of alternative healing involving psychic abilities is really going to be silenced as a purveyor of so-called medical misinformation. So maybe it seems that this slow progress towards accepting these paranormal healing techniques as real, which I've seen in my own brother, who is an MD-PhD who's gotten a whole lot of grants, has been basically surviving on grant money, studying things like this. And so he knows this research, and he knows that, for instance, prayer actually works in healing. Double blind, placebo controlled studies prove that. He knows that, and he's also a die hard materialist, and he kind of just sort of accepts it and shrugs his shoulders and so on. So there's been a lot of that kind of progress. But now with COVID and the demonization of what they're calling medical misinformation, how far back are we going to slip?

Dean Radin: Well, it's a very good question. What we all want is someone who knows all the answers. And of course we don't have that at this point. So we're kind of in a pickle. I think that's the technical term. Yes, we're in a pickle. The pickle is sour and crunchy and appealing. At the same time, some people like the pickle. I don't know that there's any—

Kevin Barrett: I like pickles. Yeah. You know, just earlier today, I was proofreading my wife's spiritual cookbook. And one of the last headlines I read before I came to do this interview was something like, "Everybody Likes Pickles."

Dean Radin: So there you go. See? So there is a certain degree of joy in the debate. And what you're describing and what we're certainly seeing now in terms of the debate in Congress, even on social media, including YouTube, is is a pickle debate about who's going to be the spokesperson for a truth that we all have to follow. And it's a very complicated topic because there are multiple truths, especially in medical science. We don't always—in fact rarely, except for fairly simple things at this point, do we understand what's going on. So I like to point out that in the domain of psychic research worldwide, total funding might be maybe $5 million through nonprofits and grants and every other source. So that's $5 million as compared to probably one hundred billion dollars being spent on something like cancer research. Well, there have been some important strides made in cancer research, but most of it's still a pretty big mystery. So the dollars turn into the number of people who are working in those fields. So if you have a field that has $5 million supporting people, you don't have very many and progress is going to be pretty slow. If you have $100 billion or more, that may be an underestimate, you have thousands, tens of thousands of people who are devoting their efforts to try to understand a very difficult problem. And if you look worldwide, then, at how much money is being spent on all kinds of interesting things in medicine and physics and whatever, we're talking probably well over a trillion dollars a year to supporting millions of scientists, all of whom are striving hard to push the boundaries of knowledge. And in the meantime, almost nothing is being spent on understanding what we're actually capable of. Because I think you're right that what we currently think of as medicine is a combination of surgery and drugs. And most of the money probably is in the drug business. At some point, I don't think we're going to need either of them. If we really understood how psychic phenomena work, I think the entire medical model will change. So having said that, now think of all of the money that's being made in the status quo in medicine and how hard it would push back on ever figuring out another way. So this is just the same old problem that we see in the academic world. It pushed back for people who made their careers based on a certain ideology. Well, along comes something that says some of that ideology is probably wrong, and there's going to be a lot of pushback. Indeed, that's OK. Having worked in this field for a long time and watching the sociology of science, anybody who gets involved in a controversial topic of any type has to expect that this is simply par for the course. So just do your work and publish it and keep going.

Kevin Barrett: Have you noticed that the politics of these topics have shifted in a very bizarre way fairly recently? It used to be that most of the people interested in, let's say, alternative healing and open to psychic phenomena and talking about them tended to be more from the political left. People on the right have tended to be a little more hidebound and often traditionally religious in a kind of obscurantist way. Today, though, we're seeing a kind of hysteria from people who think of themselves as being on the liberal or left side of the political spectrum, who are insisting on following a certain kind of authoritarian discourse with the "trust the science" motto as the centerpiece. I just interviewed a hardcore progressive comedian who spent the entire hour screaming at me to get vaccinated with enough four-Letter words to sound like she was suffering from Tourette's syndrome. So if that's the progressive left, which is what's shutting down all the debate and all of the free discussion, and suddenly it's the conservative obscurantist and to some extent Trump loving right that is where the free speech and open inquiry is, we're living in a kind of a different world from the one that I remember from just a decade or two ago. Do you have any comments on that?

Dean Radin: Historically, the the governments that supported at least the secret research in psychic phenomena were mostly Republican. The problem is that Republicans today are not Republicans anymore, at least not historically anything like what Republicans used to be. So we're in some other crazy kind of condition now where the name Republican is being used. But this is not what most people would have said was Republican even 10 years ago. So we're in a very strange place as far as the the political left or right. I think a lot of the angst comes about from doing what's good for the public, like releasing what you think is important for you and doing something for others. That's where a lot of the anger comes from. And I have to say, I agree with that. Well, an mRNA vaccine may not be the best thing in the world. It does seem to work pretty well. And each of us then has to make a decision whether we're going to stop at the red light or not. Do I want my personal freedom to do literally anything they want without regard to anybody else? Well, I would say no. I say we live in a social society. We have to consider other people as well. And so for people who don't want to get vaxxed, there's lots of reasons why people may hold that position, and that's perfectly fine, except then are they being socially responsible or not?

Kevin Barrett: Well, I would actually tend to agree with you if I thought that the data was telling us what most people think it's telling them. However, I'm not at all convinced that these vaccines slow transmission enough to make a serious difference. And there's all sorts of evidence behind that, but we won't sit here and debate that because we only have five minutes left. If you're interested, I'd be happy to send you some sources. And if not, that's fine too. And I thank you for being a lot more reasonable about the way you stated that than my interviewee Mona was, So last—we're getting close to the end—I'm really curious about how you got a blurb from John Cleese, the brilliant British comic from Monty Python and Fawlty Towers and so on. He's been one of my favourite entertainment figures, actually, since I was a kid. How did he end up blurbing your brand new book Real Magic?

Dean Radin: Well, I met John a couple of times at seminars at the Esalen Institute, and the seminars were about survival of consciousness and psychic phenomena. And John turned out to have a lifelong interest in consciousness and what it can do. So I actually found this among many creative people, because creative people tend to be more open to these kinds of experiences and actually have them. So he's one of a batch of celebrities I've met, and business people as well, who are very, very interested in these kinds of topics. And while they're not scientists or necessarily scholars about it, they're very well read. They're very interested in these issues, like most people are, and because of their status, they have the capacity to go to conferences and private meetings and that sort of thing. And that's where I met John.

Kevin Barrett: And he says that if you're skeptical of psi phenomena, start with pages 95 and 96. Well, what's on page 95 and 96 that John Cleese finds so mind-blowing? Or do we have to buy the book to find out?

Dean Radin: Well, I could be shamelessly self-promoting and say you have to have to buy the book to find out. But but what I'll say, though, is that the core of the book is: What does science have to say about the practices that we call magic? We only call them magic, things like precognition and psycho-kinetic stuff, because we don't have a better name for it yet. But these are ancient esoteric practices that have been studied in the laboratory under different names, and we find that they work. And so the core of the book is actually covering the science so that we can say with some confidence that the main practices of magic, the different categories of what's called magic, have been studied in the laboratory and they work. So this is what the the theme of my book Real Magic is all about. We are talking here about very ancient, esoteric traditions. Every culture has them. And up until when I started writing the book, if somebody had asked me, Why are you writing a book about magic? I would say, I'm not writing a book about magic. I'm writing about how science has studied some esoteric practices. But as I kept writing and doing the background research, it became very clear to me that what we call magic, of course not quite as embellished as we see in TV shows or movies, but that kind of magic actually has been examined in some detail, and we have pretty high confidence that that stuff is real. Again, not as you see in the movies, but something like that actually does exist.

Kevin Barrett: And that slogan trust the science, may or may not pertain in the field that they're deploying it for. But I think it would be a good slogan for the science of the study of psi, because if you have even probably 30 percent of the trust in that branch of scientific inquiry that you have in any other branch, you're going to be totally convinced. For some reason, there's a very strange and irrational mistrust of science in this field, as you have demonstrated throughout your work.

Dean Radin: But only by some. A lot of people do resonate with the science, especially when you describe what does it mean to trust the science, right? People use it as a slogan. It doesn't mean anything, because if you don't know how to evaluate data, then the average person who is not a scientist will look through medical journals and they can pick and choose anything they want and maybe not even understand what they're looking at.

Kevin Barrett: Mm hmm. So trust maybe isn't exactly the right word. But we should look at all scientific data as reasonably as possible and put it all on the same level, on the same playing field. We shouldn't just dismiss whole areas of inquiry because they conflict with our prejudices. So rather than saying trust the science, we should maybe say, don't mistrust the science too much. Like if I'm predisposed at this point to be skeptical about COVID vaccines, I should not just dismiss every study that seems to tell me the opposite, and vice versa.

Dean Radin: Yeah, and it's not easy, right? In order to really know what's going on with MRNA types of treatments, you'd need to know something about genetics and about how statistics are collected and what clinical trials are about, you know, the whole domain in order to actually understand what is being said.

Kevin Barrett: Mm hmm. Indeed. Ok,I think we've we've hit the end of the hour, so thank you so much. Dean Radin, author of Real Magic: Ancient Wisdom, Modern Science and a Guide to the Secret Power of the Universe. I've read two of your other books and find them very, very useful, and this one looks great as well. I'm very much looking forward to it. Thank you. Looking forward to another conversation down the line.

Very good. Okay, great. Bye.

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit kevinbarrett.substack.com/subscribe