Above is my new interview with John Friend of The AFP Report. The topic: Soros and Anti-Semitism. Below is a brief tribute to Cormac McCarthy, including my recent conversation with Linh Dinh on McCarthy’s The Road. -KB

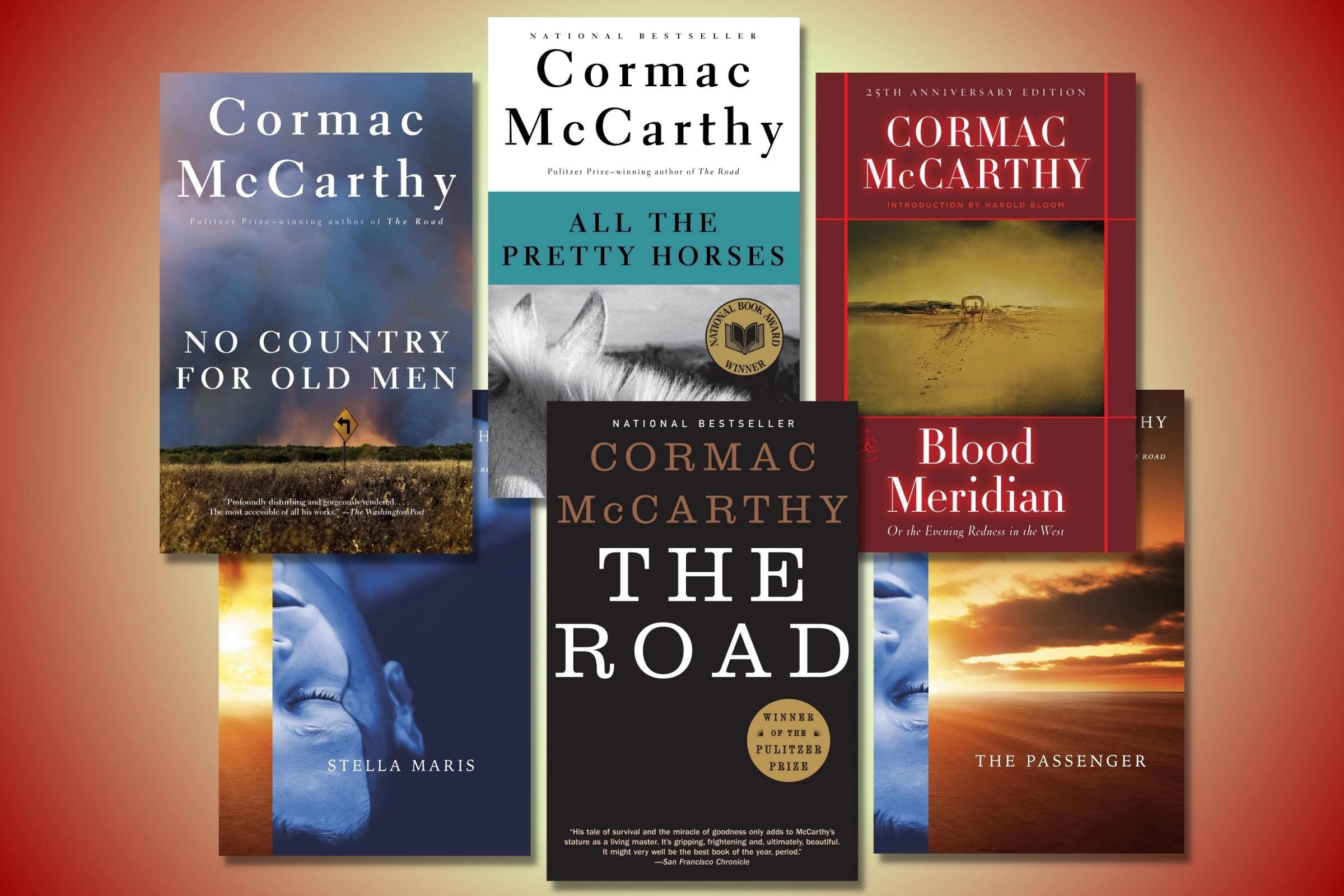

Whoever America’s greatest living novelist is, it isn’t Cormac McCarthy any more. The author of The Road, Blood Meridian, and Suttree (my three favorite McCarthy books) passed away yesterday, just over a month shy of his 90th birthday.

The three aforementioned masterpieces each depict a man’s struggle to survive. The first two paint grim, horrific pictures of existence in general and the history of the United States in particular.

The Road is where we’re headed: a post-apocalyptic hellscape. (Scroll down for details.)

Blood Meridian tells the unspeakable truth about how America was founded. It has been roundly condemned for its ultraviolence and, shall we say, moral ambiguity. But it is ourselves—and our country—that merit condemnation. Don’t shoot the messenger, especially when the messenger writes so wisely and gorgeously.

Suttree is my favorite McCarthy novel, entirely different from the other two. Unlike them, it doesn’t mesmerize you with exquisite gothic horror. Nor can it be as easily reduced to historical allegory, as Blood Meridian (America’s founding) and The Road (America’s inevitable end) can be.

If Blood Meridian describes our country’s birth, and The Road its death, Suttree is a pleasant and nostalgic—though ultimately tragic—reverie on its young adulthood. It’s McCarthy’s most autobiographical work, stringing together a series of dreamlike recollections of his younger days, when he dropped out of college, severed relations with his respectable family, and lived impecuniously on a ramshackle houseboat in the Tennessee River, catching catfish and selling them to Knoxville markets.

Though it’s bad lit-crit manners to impose your own biography on somebody else’s autobiographical novel, I must admit that I love Suttree in part because I can relate to it. As a young man, I spent quite a few years living pretty much the way Suttree does, except in a ramshackle vehicle in San Francisco instead of a houseboat in Knoxville. When I read a chapter of Suttree before falling asleep, my dreams intermingle decades-old scenes from my life with those from the book.

But I doubt one needs such an intimate relationship with Suttree to appreciate its unique genius. If Joyce set out to make the mundane mythical and amazing in Ulysses, McCarthy fully succeeded in Suttree.

By Allah or synchronicity, take your pick, Linh Dinh and I happened to open last week’s Truth Jihad Radio with a discussion of The Road. Below is a transcript of the discussion of the book.

Linh Dinh on Truth Jihad Radio

Kevin Barrett: In the first hour, my friend and colleague Linh Dinh is reporting from...well, I guess he's in Laos, last I heard. Or was it Thailand? Anyway, he'll tell us. He's written some great recent stuff, including Brave New Reset, which includes appreciations of Cormac McCarthy's The Road and Zhang Yingyu's The Book of Swindles. And well, let's just say that (second hour guest) Harrison Koehli and Linh are both in agreement that there are some serious psychopathological tendencies at play in today's so called civilization, and that things look to be getting a bit worse — maybe a lot worse, as Linh suggests. If he thinks The Road is the the way of the future, we're in even worse trouble than I realized. So let's talk about it. Welcome, Linh. How are you?

Linh Dinh: Hi, Kevin. How are you doing, man?

Kevin Barrett: All right.. Good enough to go. So Linh, I read Cormac McCarthy's The Road 10 or 12 years ago and I became a McCarthy fan. It's his grim depiction of a father and son traveling south in a desolate landscape after what appears to have been some kind of nuclear holocaust or its equivalent. It's somewhat unspecified. And the landscape is full of roaming predators and would-be pederastic rapists who would clearly target the father's son if they could get to him. There's a lot of cannibalism going on. That's pretty much how the few people left stay alive. And the sky is always gray. It's cold. Nothing's growing. And they're trying to get south where maybe there might be a little bit of sun and maybe something can grow, and maybe a couple of humans will still survive. It's quite a trip, that book, and you just wrote about that, thinking about the possibility that that vision might come true. So tell us about how you were you were thinking along those lines from Southeast Asia. By the way, are you in Laos or in Thailand?

Linh Dinh: I'm in Laos. Southern Laos. Pakse. That's the second time I wrote about the book, Kevin. But recently I thought of it again because I was drugged and robbed on the streets of Laos. Laos is so safe, you don't expect anything like that to happen. But the guy who did it was obviously not Lao. He's like a traveling con man. And I didn't expect this to happen because I was in public. I was drinking with him in a public space. I didn't expect him to put anything in my drink and then wait for me to leave. He timed this perfectly. Because I was lying on the street for I don't know how long. So that's why I thought of The Road. Because in The Book of Swindles, the still obscure Chinese book of people getting hustled, a lot of incidents happen on the road. The road is like a place in between, right? You have cities which are civilized space. That's what I thought of cities, civilization, civic citizens, all that. And the road is where bad things can happen. But in the USA it is a little bit problematic to suggest that. Because our cities, American cities, are where bad things happen right now — especially the bigger cities: Philadelphia, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Houston — just mayhem, chaos.

But traditionally, the road is where bad things happen, because no one sees what's happening. You are alone. You're meeting strangers. You get robbed, you get raped. You get killed. The book, The Road, is about that. It's about wandering: Not having a home is not having a shelter. It's about being a refugee, just a permanent refugee. And I've talked about being refugees in the past because I was a refugee.

Americans can't conceive of being a refugee. They think of refugees as just people flooding into the southern border. And many of these are not even refugees. They are "economic refugees." So they're just opportunists. But a real refugee is one who is in imminent danger. And Americans think of refugees as other people. But white people were refugees not that long ago.

So it's a theme that's constantly on my mind. You know what happens when you are forced into fleeing and you have nowhere to go because wherever you go, you're not going to be welcomed. People don't want you there.

Kevin Barrett: Yeah. And these days, your audience and maybe even to some extent my audience, includes a lot of people on what's sometimes called the alt right. And they don't really like refugees and immigration too much. And there's a marked lack of sympathy with the plight of refugees in that demographic, which always struck me as a little bit obnoxious. You could simultaneously say, look, we need to accept fewer immigrants. We'll have a better society if we have fewer immigrants. And at the same time, you could be compassionate about people who are in that situation and even maybe try to figure out a solution for them. But instead, you get all this demonization: Trump says “all those Mexicans are a bunch of rapists.” And he cites all these examples. And so people just start sort of hating on refugees. I guess that's politics, but still, it's kind of obnoxious.

Linh Dinh: Well, what's most obnoxious is that they accept no responsibility for creating refugees. Because America is the biggest creator of refugees.

I profiled an Iraqi woman barely making a living in in Scranton, Pennsylvania,and got these just basically a******s coming (in the Unz.com comment section) to rage against her, like she's coming here as a freeloader. She was working her tail off at a Dunkin Donuts factory. And she she wouldn't have been here if her life hadn't been destroyed by America, by the USA, by your tax money. You have blood on your hands.

So they accept no responsibility for that. They just see you as another brown person coming in to take advantage of them. I've had them say to me that I should be grateful. A guy (like that) recently came on to my Substack. I said: Get away from me! Because I got got sick of these idiots, man. I'm not here to f*****g entertain morons. So a guy came on to my Substack to rage at me out of nowhere. He said I should appreciate America for introducing me to air conditioning and refrigerators.

What presumptuousness! Because all his knowledge of Vietnam was from Apocalypse Now, from Deer Hunter! Vietnam was a civilized society a thousand years ago before America was even founded. And Vietnam will outlast America. And so will Laos. Laos is one of the poorest countries on earth, and they still have their tradition. They still have their values, you know, their heritage. And that's why they will outlast America, which doesn't realize how transient it is. It is a transient society. It is basically a homeless society. It's a bunch of squatters, man. They don't realize that they've been squatters and they're going to be refugees soon enough. They don't realize that they are so damn arrogant.

And I've been on that side. I'm more of a patriot than they are. Because I've been trying to do something about it. I speak up for them. And every time I do I get attacked.

Kevin Barrett: Yeah,I don't think there's a lot of political nimbleness and adroitness among that that crowd. It's funny you mentioned that, that they're saying you should be down on your knees groveling and thanking America for giving you, you poor benighted Asian savage, some air conditioning.

When I first when I first married my Moroccan wife, we sometimes used to tell people just for fun that she rode a camel to school when she was little. And with big eyes, They'd say, "Oh, really? That's so interesting." They're imagining that she was living in a tent or something.

Linh Dinh: It's preposterous. But Kevin, here's the thing, man. The collapse of the United States is really tragic, and it's accelerating. It's happening so fast, it's unbelievable. Okay. We can talk about that. You know, like the barbarity, the surging barbarity that's overtaking America.

Kevin Barrett: Okay, let's talk about that. So, The Road by Cormac McCarthy gives us a kind of a logical end point of that barbarity: The massacres and wars perpetrated by this country, which of course created all these refugees that the right wing people are always raging about, end up...well, the chickens come home to roost and the war comes home and it's a nuclear apocalypse. At least we assume that's probably the issue, or something like it anyway. And so that's it. There's not only no civilization left, but basically no life support left. And so how far down that road, as it were, are we?

Linh Dinh: Well, The Road is not clear about exactly what happened. We can assume some kind of nuclear...

Kevin Barrett: There's a flash over the guy living near Washington, D.C. and (after seeing the flash) he quickly pumped water into his bathtub before the electricity went out. It sure sounded like a nuclear war.

Linh Dinh: Right. And his wife committed suicide. That's the funny thing. And actually he didn't think that was such a bad choice, but it just wasn't his choice.

But he's still on the side of life. He’s still the father. He has to live for his son. So they're not going to commit suicide together. The mother can go and kill herself, but he's going to be the father. He's going to take care of the son.

Kevin Barrett: And that's that is a little odd...

Linh Dinh: Life affirming, huh?

Kevin Barrett: I mean, generally most mothers are just as attached to trying to keep their children alive as fathers, if not more so. So that's a little odd.

Linh Dinh: That's a very strange twist. But the theme is that they are still the good guys: They're not going to eat people.

Kevin Barrett: The last two good guys who don't eat people on earth .

Linh Dinh: So they're not going to kill anyone. At one point they heard a dog and the son said, “we're not going to kill him, are we, Papa?” Something like that. So they're not going to kill a dog. That's not very realistic, is it? But the fact that they still have values is important. That's the main theme of The Road: Whatever happens, they're going to remain humans. They're not going to kill or eat people. And at the end, the son has his faith restored because they encounter this apparently Christian family who's going to take him in. So that's the positive message of The Road.

Still, the book is very bleak. When the father reflects on the state of the world inside the novel, he seems to have no faith: deep down, he realizes this is just futile. This is just hopeless. But he doesn't have a choice but to go on for the sake of his son. What is he going to do, kill his son and kill himself? He's not going to do that. So it's a very desperate faith. And I'm wondering where we are right now as far as our faith in anything — in civilization, in ourselves.

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit kevinbarrett.substack.com/subscribe

Tribute to Cormac McCarthy